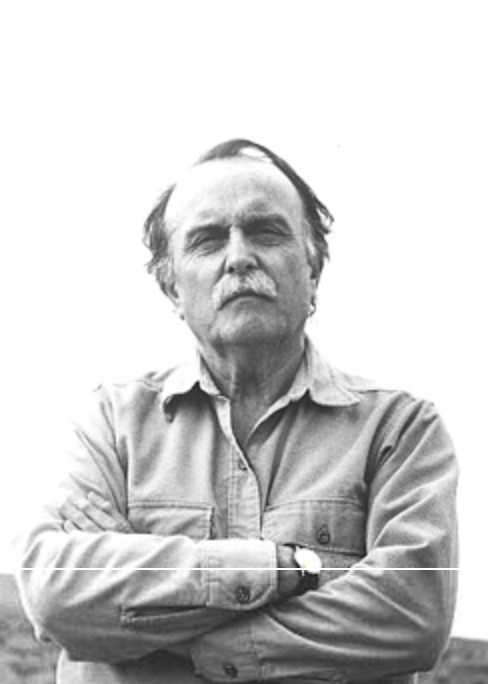

Alvin Lucier and player-agency

The work of Alvin Lucier is notable for its focus on sonic phenomena, harnessing material agencies for their indeterminate qualities. Lucier takes a (Cagean) non-interventionist approach to material agency, preferring to let phenomena speak for themselves. Works such as I am Sitting in a Room (1969), and Music on a long Thin Wire[1] (1977) are set up and then run on their own as a process of interaction between materialities. The successful performance of these pieces is heavily dependent on what Pickering refers to as ‘tuning’ in order to get the balance of agencies right to maximise focus on the phenomena. As a simple example, care must be taken in setting up I am Sitting in a Room to avoid the feedback process happening too fast or too slow; resulting (respectively) in either the rapid collapse of the piece into a single dominant feedback tone, or the feedback failing to build-up due to inadequate gain control. Thus the successful setup of this piece requires an attunement to the specifics of the situation; 'this' loudspeaker, 'this' amplifier, 'this' room, etc. Music on a long Thin Wire is both is more complex—sonically and agentially—but also more forgiving. More forgiving because the score has no a priori teleology to work towards (the sound simply continues) and any variations in that sound are acceptable; that is, excluding the total-collapse of vibration, or inclusion of additional sounds caused by direct human intervention in performance. While Lucier’s first versions of this piece required human intervention periodically to create ‘phrases’ by altering the amplification, Hauke Harder explains how this was unnecessary because Lucier ‘found out that the wire, when carefully tuned, got a “life of its own” and showed various acoustic phenomena’.[2] Once the correct balance of things (magnets, wire-tension, amplification) is achieved, then the piece is autopoetic.

In both of these examples, once the dance of agency (Pickering 1995) has been appropriately tuned then the material agency is left to play-out, and this play is the performance of the piece. Expanding on that scenario, I turn to Lucier’s Music for Cello with One or More Amplified Vases (1993) where the dance of agency happens in the setup period but also continuously across the moment of performance. Here, a set of vases are amplified and a cellist ‘slowly and continuously sweeps up the range of the cello, searching for resonances in the vases which are picked up by the microphones and made audible for listeners.’[3] Material agency is tuned in the setup of this piece by positioning the various things (vases, microphones, loudspeakers) and sound-levels so that the cello can meaningfully interact with the vase resonances in the space. In performance, the cellist is situated (via the score) largely as a neutral frequency-sweeping device whose role is to locate and reveal resonances of the vases; as noted above, the score specifies that the player’s role is ‘searching for resonances in the vases [to be] made audible for listeners.’ While the central score instruction constrains the player in this neutral role, the score also allows for a more open human agency with the following: ‘From time to time stop and explore certain resonances by slightly varying the pitch and amplitude of your bowing’.[4] This clause provides some freedom for the player, but not to do what they like, rather this choice of words is designed to ensure the cellist does not expand their role by foregrounding themselves. The cellist’s action must be sparingly applied (‘From time to time’), and the adjustment to normal continuous sweeping movement is ‘slight’. The intention here is clearly that the cellist’s role is supportive and facilitative, lingering on a resonance to increase its presence, foregrounding the material agency of the vase.

Lucier makes this point explicitly in many of his interviews. Talking about Music for Solo Performer (1965), Lucier says; ‘Discovery is what I like, not control. I’m not a policeman. […] the composition was then how to deploy those speakers, what instruments to use’.[5] Here he situates the compositional act in how the energy of the amplified brain-waves is distributed to different instruments, a timbral and spatial orchestration of the phenomena. In a 1989 interview with Daniel Wolf, Lucier states that his ‘problem with instruments is to keep their playing clear and simple so that the acoustical phenomena are as clear as possible.’[6] The foregrounding of the material phenomenon and its contingent behaviours drives Lucier’s composition, and the human agency accommodates the material agency in order to facilitate the phenomena. This can be seen in these further examples from scores:

- 'Search for harmonics, internal rhythms, and other unexpected acoustic phenomena’. Music for Snare Drum, Pure Wave Oscillator, and One or More Reflective Surfaces (1990).

- ‘The amount and quality of the sonic activity should be regulated by the ability of the flame to respond’. Tyndall Orchestrations (1976).

- 'Use the directional properties of the binaural system to localise the phenomena for listeners'. Bird and Person Dyning (1975).

- ‘play long tones that excite the resonant frequency of the object most effectively. Once a tone has been sounded make no adjustments in intonation; instead, let discrepancies in pitch cause audible beats and other acoustic phenomena’. Risonanza (1982).

- 'Sweep with microscopic slowness so as not to miss any possible pattern and with continuous motion so as to make an accurate mapping in time of all resonant, sympathetic, pendular, sonic, and visible phenomena’. That extract is from the concert version, note also the installation version from the same score, in which the sine waves stay the same but environmental factors (such as air humidity and temperature) alter the drumhead response and create variation in the pendular motion. Music for Pure Waves, Bass Drums and Acoustic Pendulums (1980).

Not all of Lucier’s pieces have an explicit material agency to foreground. His works involving (human) musicians often centre on the phenomenon of acoustic beats in way that doesn’t have a specific materiality other than the interaction of frequencies in the air. This phenomenon, while explicitly foregrounding the physicality of sound-as-moving-air, doesn’t exhibit much in the way of material indeterminacy since air is a relatively neutral medium. While Music for Cello with One or More Amplified Vases definitely has a sonic focus on beats, the player must negotiate the materiality of the vases—and the amplification—to achieve this. Other pieces such as Crossings (1982), In Memoriam John Higgins (1984), and Charles Curtis (2002) are written only for instrument(s) and sine tone, creating the beating phenomenon through interaction of held tones in the instrument with a slowly moving sine tone.[13] These pieces don’t foreground indeterminacy, but it’s interesting to note that engagement with the material phenomenon is still a key aspect of performance. Anthony Burr’s account of performing Lucier’s In Memoriam John Higgins describes how his performance practice moved away from the notes and towards the sound phenomenon. Burr states:

"So I rethought everything about how I was going about preparing and performing the piece. First, and most importantly, I never practiced the long notes alone again. I only practiced the piece with the sine wave. This felt explicitly like a shift in focus of execution from direct realization of the score to direct realization of the phenomena underscoring the piece."[14]

The formal organisation of In Memoriam John Higgins and similar works is highly procedural, which is another strategy for focussing attention—of player and audience—on the revealed phenomenon. Justin Yang describes Lucier’s instrumental material as ‘generative’, noting that ‘what the orchestra plays [in Diamonds (1999)] has to be strictly generative, and as catalytic and generative agents they cannot exert themselves musically. Once they become gestural or expressive the whole nature of the work changes’ [emphasis in original].[15] Musicians play generative parts because their function is as near-neutral support-agents who interact with sine-waves to produce phenomena: the lively thingliness in Lucier’s work is in the interaction of sounds, not the sounds themselves. Performers in Lucier’s work are generally not granted traditional modes of expression, instead they work directly with the phenomenon. This is not to say that musicians are in some way less important or undervalued by Lucier, he simply offers a different approach to the conventional mode of expressive engagement—manipulation of material—into something more recognisable as Ingold’s mode of ‘working with materials and not just doing to’.[16]

As mentioned above, in Music on a Long Thin Wire, Lucier shifted away from his initial attempts to procedurally structure the piece, choosing instead an open form whose emergent structure is contingent on material fluxes in the wire’s oscillation over time. The wire, with the support of the system of amplification and magnetics, has sufficient thing-power to generate music. As Yang describes it: ‘Rather than a need for formal organization, Lucier’s materials express a potential for formal generation which, it seems, is inscribed in the very nature of the material itself [emphasis in original].’[17] Yang’s ‘potential’ is a good descriptor for material indeterminacy since it inheres in the thing if not agency then certainly the mechanics of lively and complex interactions. And that’s what this article is about…composing for such situation.

[1] Here I refer to the later-developed installation version, not the concert version described in the score (see Lucier, Reflections, p. 374).

[2] Hauke Harder, ‘Music on a Long Thin Wire: Music as a Self-Driven Process?’, Leonardo Music Journal (online supplement), 22 (2012), p. 1

[3] Alvin Lucier, Reflections (Cologne: MusikTexte, 1995), p. 410

[4] Ibid.

[5] Alvin Lucier, cited in Volker Straebel and Wilm Thoben, ‘Alvin Lucier’s Music for Solo Performer: Experimental music beyond sonification’, Organised Sound, 19 (2014), 17–29, p. 26

[6] Alvin Lucier cited in Anthony Burr ‘Between Composition and Phenomena: Interpreting “In Memoriam John Higgins”’ Leonardo Music Journal (online supplement), 22 (2012), p. 2

[7] Lucier, Reflections, p. 408

[8] Ibid., p. 354

[9] Ibid., p. 372

[10] Ibid., p. 392

[11] Ibid., p. 390

[12] What little resonance air possesses as a medium is essentially the same across the range of pressures that humans might encounter it, so air has little or no resonant topology that might provide resistance or unpredictable energy movement.

[13] Note also pieces like Slices (2007) which achieves the beating without sine tones, using instead the simultaneous sounding of the same pitch in equal tempered and just intonation versions.

[14] Anthony Burr ‘Between Composition and Phenomena: Interpreting “In Memoriam John Higgins”’ Leonardo Music Journal (online supplement), 22 (2012), p. 6. Note here that Burr’s reference to the ‘score’ means the pitch notation, not the prose instructions. While Burr notes earlier that Cagean experimental music can have the perspective that ‘the "work" exists in the set-up or the instructions […] and that the experience was whatever follows from the execution of those instructions’ (ibid. p. 5) pieces like In Memoriam John Higgins and other beating pieces tend to be fully notated and not rely on extensive prose instruction (as the piece for cello and vases does). For the performer not well-versed in these pieces and their practice, material agency can be accidentally sidestepped by focussing on the written pitches when the essence of the piece is hidden away in prose instructions.

[15] Justin Yang, ‘Semiotics, Presence and the Sublime in the Work of Alvin Lucier’, Leonardo Music Journal (online supplement), 22 (2012), p. 3

[16] Tim Ingold, Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description, (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011), p. 10

[17] Ibid.